DRAMATIC FACIES CHANGES, LOW RESISTIVITY, AND SIGNIFICANT TIGHT GAS POTENTIAL

The Cotton Valley Group is a subsurface wedge of Late Jurassic (Tithonian) clastics in the greater Mississippi/Alabama area that grade downdip (generally, in a southwestern direction) into a series of marine shales and carbonates in the southwest corner of Mississippi and the southeast (Florida Parishes) area of Louisiana. There is mounting evidence that suggests the deposition of the Cotton Valley - especially in eastern Mississippi - coincided with a period of intense basement tectonic activity associated with compressional/extensional (transpressional/transtensional) regimes, initiated by strike-slip (wrench) faulting. In western Mississippi, the depositional cycles within the thick Cotton Valley are less affected by basement movement and more influenced by salt tectonics; accordingly, facies and isolithic changes are less abrupt and easier to follow.

The nomenclature applied to the subdivision of the Cotton Valley in Mississippi has been problematic, given its origins in Northwest Louisiana. It is easy to understand why distinct facies of the Cotton Valley in that area become less distinct as one moves several hundred miles east to south-central Mississippi. The post-depositional uplifts of the Monroe-Sharkey Platform and the Jackson Dome (as but two examples) resulted in large areas where much of the entire Jurassic section - including the Cotton Valley - was eroded (beveled) off by a succession of unconformities, culminating in the dramatic angular unconformity at the base of the Tertiary. South of the Monroe-Sharkey Platform, in eastern Louisiana, the Cotton Valley plunges to depths greater than 20,000 feet subsea, resulting in a rapid loss of subsurface control as one approaches Mississippi from the west. Accordingly, the subsurface geologist must make certain assumptions about correlations within the Cotton Valley as he or she presses east and south from the well-known Cotton Valley trends of Northwest Louisiana.

In most of South Mississippi the Cotton Valley sediments penetrated by the bit have been assigned to the Schuler Formation. The downdip shale equivalents observed in Southwest Mississippi could thus be attributed to the Hico Shale of North Louisiana, with the possibility that a Bossier Formation equivalent exists as well in the extreme southwest corner of the state and along the western perimeter of the Wiggins Arch (in portions of Pearl River and Hancock Counties).

Generally speaking, most subsurface geologists in Mississippi tend to pick the top of the Cotton Valley Formation at the base of the basal transgressive sands of the overlying Hosston Formation (at the Lower Cretaceous (LK) / Jurassic Unconformity, which is a disconformity in most of the subject area). In much of South Mississippi, this disconformity is readily observed on electrical logs as the base of a thick gravel-bearing (cherty) sandstone. In areas where the Hosston gravels are thin or absent, geologists will choose the top of the highest substantive shale in the Upper Cotton Valley as the formation top, or the top of a typically thin limestone. It is unclear whether this limestone is the stratigraphic equivalent of any similar Upper Cotton Valley limestone unit mapped in North Louisiana.

The base of the Cotton Valley is typically picked at the disconformity located at the top of the Haynesville Formation (Lower Tithonian - Kimmeridgian). The lithology of the Upper Haynesville Formation varies considerably across the South Mississippi area; in some areas, it is a carbonate, but in other areas, it is an anhydritic shale or an even more evaporitic sequence (an anhydrite bed, or a series of anhydrites interbedded with shales). Generally speaking, in most areas the base of the Cotton Valley / top of the Haynesville is definitive, with an abrupt lithologic demarcation (i.e., thick sands atop a thick anhydritic shale sequence). In other areas, the transition is much more subtle - even difficult; what appears to be distinctly disconformable elsewhere appears to be "locally" conformable. Such problematical areas include the Smith /Jasper/Clarke County area, where thin carbonates interfinger with and (in some areas) segregate sandstones in the Lower Cotton Valley and underlying Upper Haynesville in a rare, potentially conformable transitional sequence that challenges regional correlations and gives rise to sub-regional nomenclature (examples include the "Bay Springs" and "Griffin" Sands). Where the interfingering carbonates persist across a structural uplift of Jurassic age, hydrocarbons (sourced from the underlying Lower Smackover Brown Dense Limestone) can become trapped beneath those sub-regional topseals, resulting in the formation of important reservoirs such as those encountered at Bay Springs, Tallahala Creek and McNeal Fields.

Compressional basement tectonics associated with wrench faulting and the provenance of Appalachian Valley and Ridge contributed to the deposition in Southeast Mississippi of a thick arkosic sandstone in the Lower Cotton Valley (stratigraphically, considered just above or, alternatively, updip of the afore-mentioned Bay Springs and/or Griffin Sand equivalents). This arkosic facies, informally dubbed the "Pink Sand" by some geologists and the "Lower Cotton Valley Massive Sand" by others, appears to comprise sediments eroded, in an arid environment, from the adjacent ridges (compressional folds) of the Appalachians. The arkose is generally thickest in the synclines (valleys) of the Appalachians (originating as a series of coalescing alluvial fans), and where movement along wrench faults created transtensional synclines. It follows that the Lower Cotton Valley arkose thins dramatically over the Appalachian Ridges and the transpressional thrusts formed along the compressional component of the wrench faults. This isolithic relationship is most readily observed in Scott, Smith, Jasper, and Clarke Counties in Mississippi and in the adjoining Choctaw County, Alabama.

The presence of frosted sand grains within the sub-regional Bay Springs and Griffin Sand equivalents of the Lower Cotton Valley suggest eolian transport, and there has been considerable debate among geologists as to the depositional setting under which these sandstones were deposited. The tendency to immediately attribute such frosted sand grains to a sand dune geomorphlogy is understandable but so generalized as to be simplistic. It is probably more accurate to suggest that sand dunes were but one component of an arid to semi-arid near-coastal environment within which wind and water (fluvially, via wadis, and littorally, via moderately high-energy longshore and rip currents) combined to transport, rework and redeposit the abundant arkosic sediments as the Bay Springs and Griffin Sand equivalents in the Jasper County area. Such a geomorphological concept, characterized by episodic fluctuations in sea level, could account for the interfingering carbonates, frosted sand grains, and occasional siltstones that are observed in the basal part of the Lower Cotton Valley.

In west-central Mississippi, it appears a second source of clastics - this time, from the north - contributed a substantial volume of additional sediment to the Cotton Valley. This source appears to consist of several Cotton Valley nearshore and delta complexes fed principally by an ancestral Mississippi River. The contribution of sediments from this second source serves to greatly increase the percentage of sand within the overall Cotton Valley interval in west Mississippi (as opposed to South-Central Mississippi), and this clastic pulse persists well into the Warren/Western Hinds/Copiah County area.

Moving further west and south, the Lower Cotton Valley arkose grades laterally into a predominantly shale section with numerous interbedded sandstones that generally average 20 to 50 feet in thickness. In extreme south and southwest Mississippi, the entire Cotton Valley becomes more marine and the few sandstones that persist are thinner with less porosity and permeability than their updip equivalents. There are numerous siltstones within this interval, which can be considered the lateral equivalent of the Bossier; unlike its Northwest Louisiana counterpart, the Bossier equivalent in extreme south and southwest Mississippi has been buried to great depths (typically deeper than 18,000 feet). Deep Jurassic subsurface (well) control in those areas is admittedly sparse, and poorly understood.

The type of hydrocarbons encountered in the Cotton Valley varies somewhat predictably with depth, with the oil reservoirs being confined to the moderate depth fields in the southeastern area of Mississippi. The deepest commercial oil reservoir is found at Collins Field, in Covington County. The deeper reservoirs to the south and west grade from gas and condensate (examples being Mechanicsburg, Bolton, and Newman Fields) to dry gas (Catahoula Creek in Hancock County, and Bogalusa Field in neighboring Washington Parish, Louisiana). Oil and gas produced from the Cotton Valley (all of which is sourced from the underlying Smackover Brown Dense Limestone) is typically sweet, with little hydrogen sulfide. Appreciable volumes of carbon dioxide are found in the Cotton Valley only in very specific, localized areas of West-Central Mississippi, sourced not from the Smackover but from the mantle via basement wrench faulting. The only Cotton Valley gas reservoirs known to contain significant amounts of hydrogen sulfide are found at Catahoula Creek Field, presumably the result of deep burial depth and a locally-elevated temperature gradient.

In several areas of the Cotton Valley Producing Trend, the presence of chlorite and other similar interstitial clays causes the producing resistivity to drop to as low as one ohm-meter, thus creating subtle, low-contrast / low-resistivity oil and gas reservoirs. These low-contrast reservoirs are readily observed within the updip oil producing province of Jasper County and the downdip gas producing province of southern Yazoo and western Hinds County. This is intriguing since it would appear that the Cotton Valley sediments of the updip oil producing province of Jasper County were derived from an Appalachian source, whereas the Cotton Valley sediments of the downdip gas producing province of southern Yazoo and western Hinds County were probably derived from a different (Arkansan?) source.

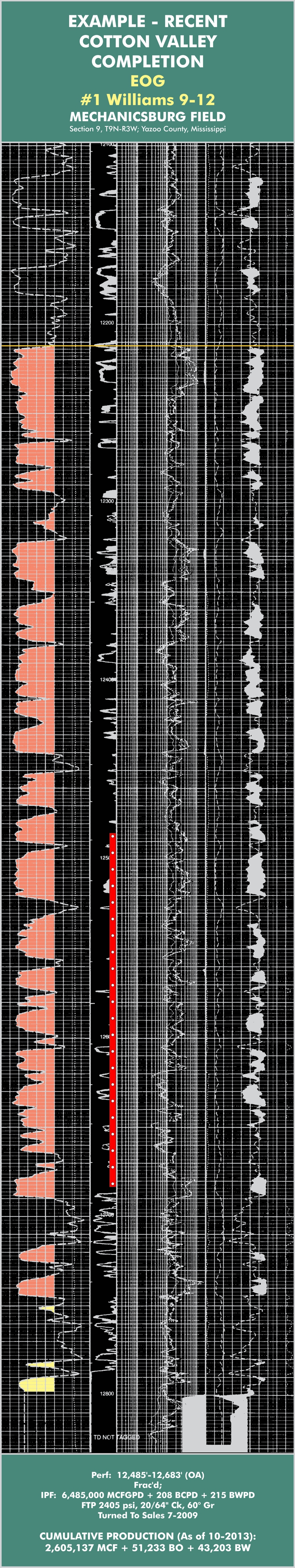

Wells completed in the downdip, less porous and permeable sandstone reservoirs of the West Mississippi Cotton Valley Gas Trend have only been stimulated with modern multi-stage fracture treatments within the last five years. Such multi-stage "fracs" have been highly successful at Mechanicsburg Field (in Yazoo County) and Bolton Field (in Hinds County). Severe reservoir compartmentalization limited the effectiveness of the Cotton Valley fracs in the Bolton Field wells (with reservoir sizes less than 30-40 acres). In areas where reservoir compartmentalization is not an issue, it would appear that the modern multi-stage frac is a very effective completion procedure; accordingly, considerable tight gas resource potential remains within the Western Mississippi Cotton Valley Gas Trend.

In addition to the log example from Mechanicsburg Field that is shown immediately after (below) this discussion, click here to view a second example; this one initially completed FARO 10.5 MMCFGPD + 212 BCPD.

Hydrocarbon entrapment within the Cotton Valley is directly related to the percentage of sand to shale. In areas where most of the Cotton Valley interval is comprised of sand, as one would expect only anticlinal (four-way) closures and (three-way) salt wall truncation traps harbor the potential to produce significant reservoirs. Conversely, as sand percentages decrease (generally as one moves in a downdip direction), numerous fault-juxtaposed and stratigraphic traps are observed. It is therefore important for the exploration geologist to possess a reasonably good understanding of the distribution of sand within the Cotton Valley when assessing exploration risk within the area of interest.

Steve Walkinshaw, President, Vision Exploration

This entire site Copyright © 2017. All rights reserved.